021: we too are in space

Every space story is about humans—and the most intimate parts of being a human. They're about loneliness, about how our perception of time changes, about how we see life, about the scale of it all. We explore the infinite beyond, in order to find answers to the infinite within. We go beyond the edges of what we can survive in, to understand the bits of ourselves that make life what it is. But we too are in space. The Earth is not outside of space, it too is in space. We are all in space.

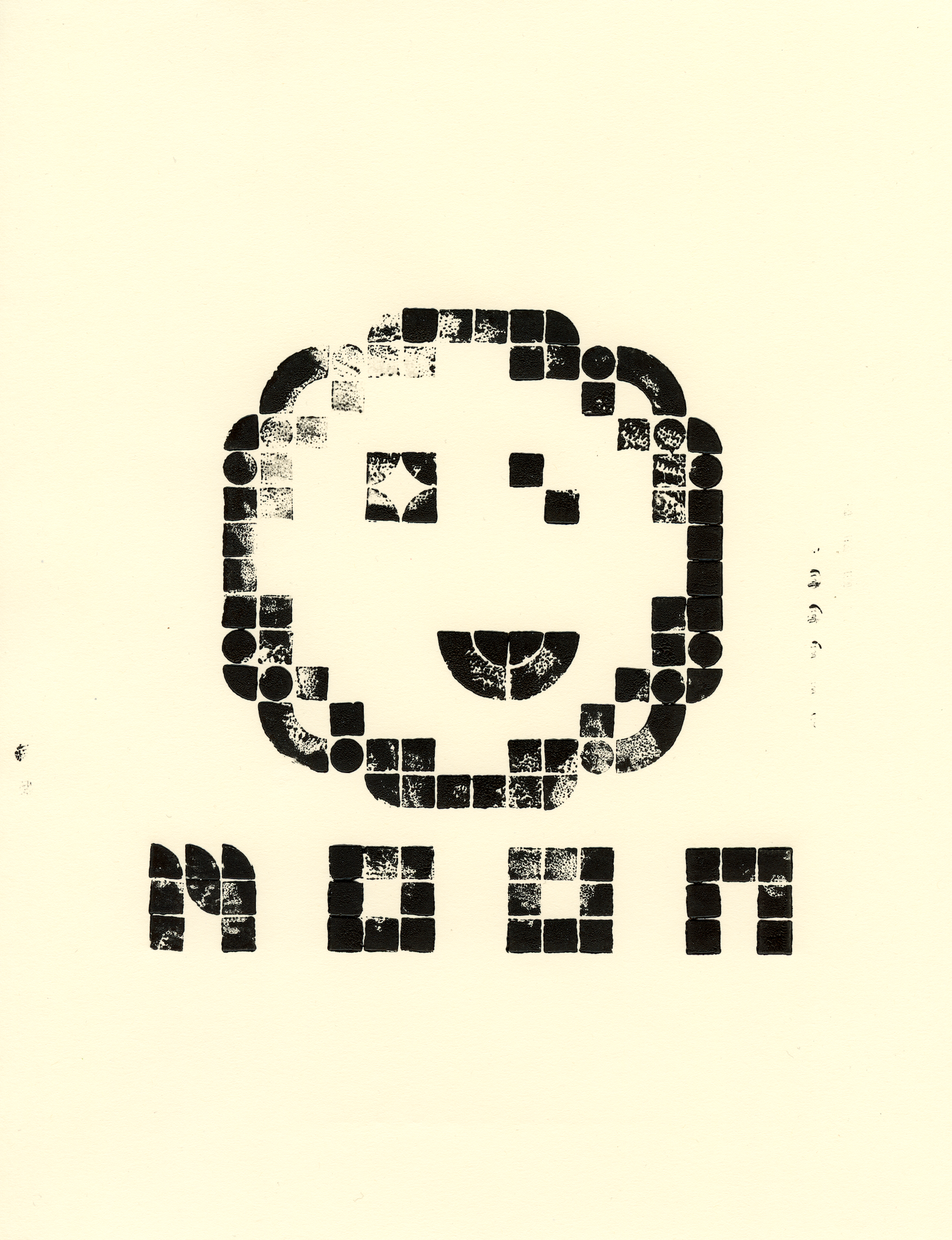

Remember the printers in Office Space—printing as a representation of work, but if instead printing can be play?

I arranged some LEGO bricks to create a moon and used that to create a relief print on paper. By just applying screen-printing ink on top of the LEGO bricks (which were affixed to a larger LEGO board), a playful printing press is made.

A toy is on its way to the moon, because we don't even play on Earth anymore. Why do we have to go to the kids' toy aisle to find things to play with?

There are LEGO sets for adults, and a lot of adults do like LEGO, but is that even play? Sets designed for adults focus on making something that is nice to display, instead of embracing the inherit advantage of the LEGO brick, that it can be constructed and deconstructed. Likewise, adult kits have specific and elaborate instructions to create something that is semi-realistic. Compare that to LEGO for kids, where there might just be a bunch of bricks for kids to make something with, or even if there are instructions, they act more as templates to build abstractions of an object because the constructions are usually too simple to realistically depict real-life objects. (This may be less true now, as it seems LEGO for kids and adults are now really focused on licensed, instruction-based kits.)

The difference reveals the shift in focus, less on the playing aspect, and more on achieving the end build. The focus on realism and complicated instructions are both devices to move someone away from imagining, and into the narrow scope of skill-building. We are deluded into thinking that as adults, play is the rewarding sense of accomplishment from using our time productively instead of play as this expansive playground to create worlds and imagine possibilities. We've traded the ephemeral infinites of creating and destroying and creating and destroying, for the opportunity to follow instructions once to create a trophy for a licensed world that is not imagined, nor owned by the person constructing it. Our power to play, to construct something out of an empty canvas, has been robbed, replaced by the soulless duplication machine that we project printers to be.

Georges Méliès' A Trip to the Moon, the iconic film that crammed a bunch of special effect ideas into less than 20 minutes, still feel fresh today. It's brimming with creative ideas even though over a century of filmmaking and filmmaking technology has "progressed" since. I think part of it was that film wasn't taken as seriously then. A Trip to the Moon fell into the sub-genre of trick films, little experiments with light and video, something like a parlor trick, but also something just a bit playful. And I think that play was and is key.

Finishing the website trilogy of exploring space in a website, SPACE is the bench that SETTING speaks of (well all three tiny.sites are virtual benches of sorts).

Why does every website have to do something, why do we always have to do something when we are online? Why did we have to shift from online beings into computer users? With SPACE, I offer an abundance of space, so much space that we don't know what to do with. And I think it's okay to be overwhelmed for a bit. Whenever it gets brought up that most of outer space is "empty" space, why are we alarmed? Why do we presume it's a negative thing, or that it means that we're lonely out here? The space is not even "empty", it's just full of what we struggle to wrap our heads around. Even in emptiness, there is a fullness.

I think about how Phil Christman talks about flatness in Midwest Futures, flatness here talking about the flatness of the Midwest, as a featureless destination, as a boring reality, as an empty landscape: "What flatness actually means is excess, overwhelm. By not hiding any of itself, a flat place exhausts your seeing. It gifts us more information than we can take in; dazed, bedazzled, we give up on it, and call our failure boredom."